iPhone Camera: How to control focus and depth of field

![]() One of the most striking differences between your iPhone and a large camera like a DSLR is the way the two cameras focus and control depth of field. In a DSLR, depth of field is easy to manage by changing the aperture—a large aperture like f/4 results in a relatively narrow field of focus, for example, while a small aperture like f/20 delivers deep depth of field in which most of the photo is in focus.

One of the most striking differences between your iPhone and a large camera like a DSLR is the way the two cameras focus and control depth of field. In a DSLR, depth of field is easy to manage by changing the aperture—a large aperture like f/4 results in a relatively narrow field of focus, for example, while a small aperture like f/20 delivers deep depth of field in which most of the photo is in focus.

On the iPhone and other smartphones, though, you don’t generally get that kind of flexibility. Without an aperture dial, you get little control over your depth of field. And thanks to the laws of physics, the tiny sensor results in a large depth of field in most of your photos.

You don’t have to be satisfied with that, though. Take control of your iPhone’s focus to capture the photos you want to achieve.

Specify the focus

This is hardly a state secret: All but absolute iPhone beginners know that you can tell the phone where to focus by tapping on the screen. If you want the foreground in focus, tap on something close to the camera. Want the background in focus? Tap a background subject. If most of the objects and people are about the same distance from you, this won’t matter very much, and you can rely on the phone’s autofocus to do the work for you. But if you have something very close and somewhat distant, you can definitely affect what’s in focus.

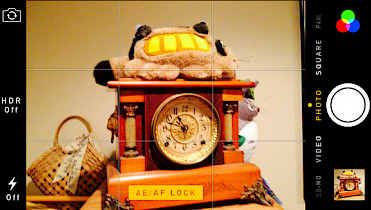

Tap and hold to lock the focus with the Camera app.

Separate focus and exposure

The problem with that common trick is that the iPhone sets both exposure and focus with the same tap. If your foreground subject is also dark, you can end up over-exposing the photo. To solve that problem, install a better camera app – popular favorites include Camera+ ($2) and Top Camera ($3). Using either of these apps, you can tap separately to focus and specify where to set the exposure. The end result: You no longer have to live with under- or over-exposed photos just because you chose to set the focus point.

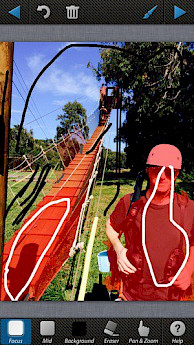

AfterFocus lets you adjust the parts of the image you want to focus after the fact.

Lock the focus

You don’t need to install a new camera app to take advantage of this fancy focusing trick: You can lock the focus on the iPhone sort of like holding the shutter release button halfway down locks focus on a traditional digital camera. Tap and hold a spot on the screen for a few seconds until you see a yellow box flash around your finger. Let go, and you’ll see the message “AE/AF Lock” on the screen. You can now re-compose the shot, and the focus and exposure will remain the same until you tap the shutter release button.

FocusTwist shots a short video and then shows you a still photo derived from it.

Simulate a DSLR’s depth of field

The smaller a camera’s image sensor, the larger the depth of field it creates. That’s why smartphones and compact digital cameras can’t compete with Digital SLRs when it comes to taking photos with romantically blurred backgrounds. There’s help, though. Try an app likeAfterFocus ($1). Open an existing photo or take a new one, and then outline the areas that you want to be in sharp focus and in blurry relief. The app then blurs the background for you, giving you a convincing shot with simulated depth of field.

Control depth of field after the fact

One of the wonders of modern engineering is a camera known as Lytro—it uses a sophisticated array of sensors to capture sharp focus everywhere in the scene at once.

Afterwards, using special software, you can change the focus point just by clicking. Want the background in focus and the foreground blurry? You can do it in one click, and then change your mind as often as you like. You can simulate that same effect on your iPhone with FocusTwist ($2). This app shoots a short video of a scene and presents it as a still image. When you tap in the image, it changes the scene to show that part of the scene in focus. You can also share your variable-focus creations online.

For professional and affordable IT tech support, feel free to contact us at Farend, for no obligation consultation.

The above article was originally published by Macworld and can be seen here.